Molly (Millie Perkins) and her sister, Cathy (Vanessa Brown), have conflicting memories of their father. Molly believes he’s a brave captain lost at sea because he was too good a man to live on land. That’s what she tells her nephews, Tadd (Jean Pierre Camps) and Tripoli (Mark Livingston), and that’s what we believe until Cathy rudely corrects her in front of the children. She claims he was a drunken bum and an evil bastard. One of them is right, and if flashbacks from the women’s childhoods is considered reliable evidence, it’s Cathy.

The fact that Molly romanticizes her relationship with her father is only one indication of her mental state. She seems obsessed with male beauty; however, when watching two hunks working out on the beach, she imagines them dead, either hung by gymnastic rings or crushed under barbells. My interpretation is that these men didn’t really die and that Molly is not literally a witch. Later, though, when she has visions of handsome, naked men dying gruesome deaths, they’re real, sending two detectives hot on her trail.

Specifically, as she’s doing shots before going to work at a local bar, she fantasizes about two “beautiful” football players that she ties to the bedposts, encourages to climb on top of each other, and then castrates. She arrives late to her job at 10:00 and we later learn that two football players died… at 9:30. She’s similarly attracted to two other men she finds “beautiful” on television: Alexander McPeak (Stafford Morgan), an actor from a razor blade commercial, and Billy Batt (Rick Jason) an aging actor.

If we have any doubt by this point that Molly is a little unhinged, she denies that anyone has been killed unless she sees it on TV. “You can’t believe anything unless it’s on TV.” I don’t recall whose bed she’s crawling out of when she says this. She seems to be in a long-term relationship with the bar owner, Long John (Lonny Chapman), but seeks the company of McPeak, while Long John arranges for her to be company for Batt. She also doesn’t like to wear her shirt; it’s often open or gone entirely.

During the middle part of The Witch Who Came from the Sea (1976), I was texting my brother with some of the lurid details, telling him that it was an independent horror film from the 1970s that was dripping with the era. Obviously, the movie was not holding my attention. However, soon after that, as the dialogue became more ridiculous with Molly spinning further out of control, I became more intrigued. There was something raw and natural, about it, like a flowing stream of consciousness.

It reminds me in some ways of Messiah of Evil (1974), but while it shares a similar look and feel, it doesn’t have the same dark, creepy atmosphere. Witch is more blatant, while Messiah is more mysterious. As bizarre as it gets, there’s something compelling about the sisters that grounds the movie. You don’t know exactly what their childhoods were like, but we’re given enough information to imagine, and it’s psychologically fascinating how they turned out. Did Cathy share Molly’s abuse, or was she only witness to it?

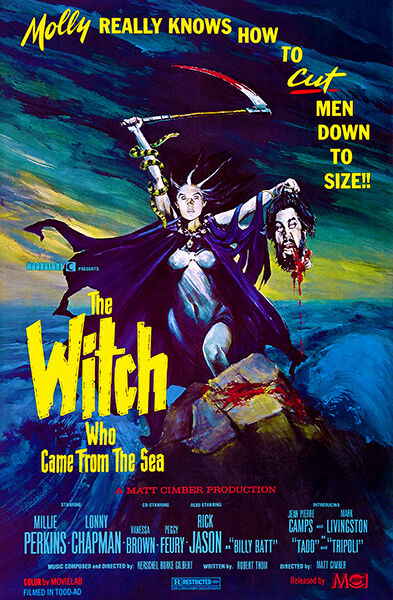

At the point I was texting my brother, I would never have recommended The Witch Who Came from the Sea; however, I now believe I would. It’s rough in all the areas that normally make a polished film, but that’s what makes it sincere. More sexually explicit than gory, the screenplay by Robert Thom and direction by Matt Cimber work together to create an overall eerie experience. Cimber later directed Butterfly (1981.) I haven’t seen that one, but after watching this, I can envision him being the perfect person to make a movie starring Pia Zadora.

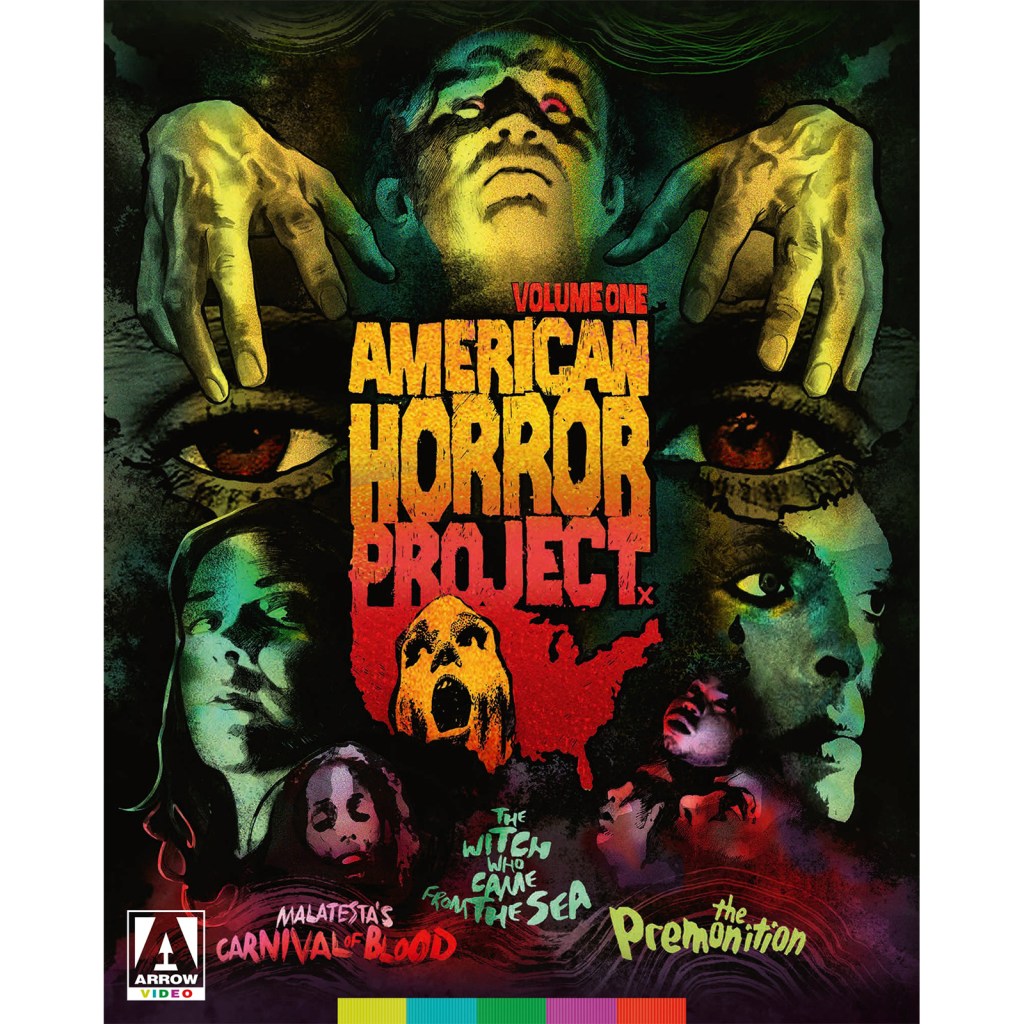

2026 marks the 50th anniversary of the release of The Witch Who Came from the Sea, which opened on January 2, 1976, in Corpus Christi, Texas. It’s now available on the Arrow Video Blu-ray box set, The American Horror Project Volume 1.

Leave a comment