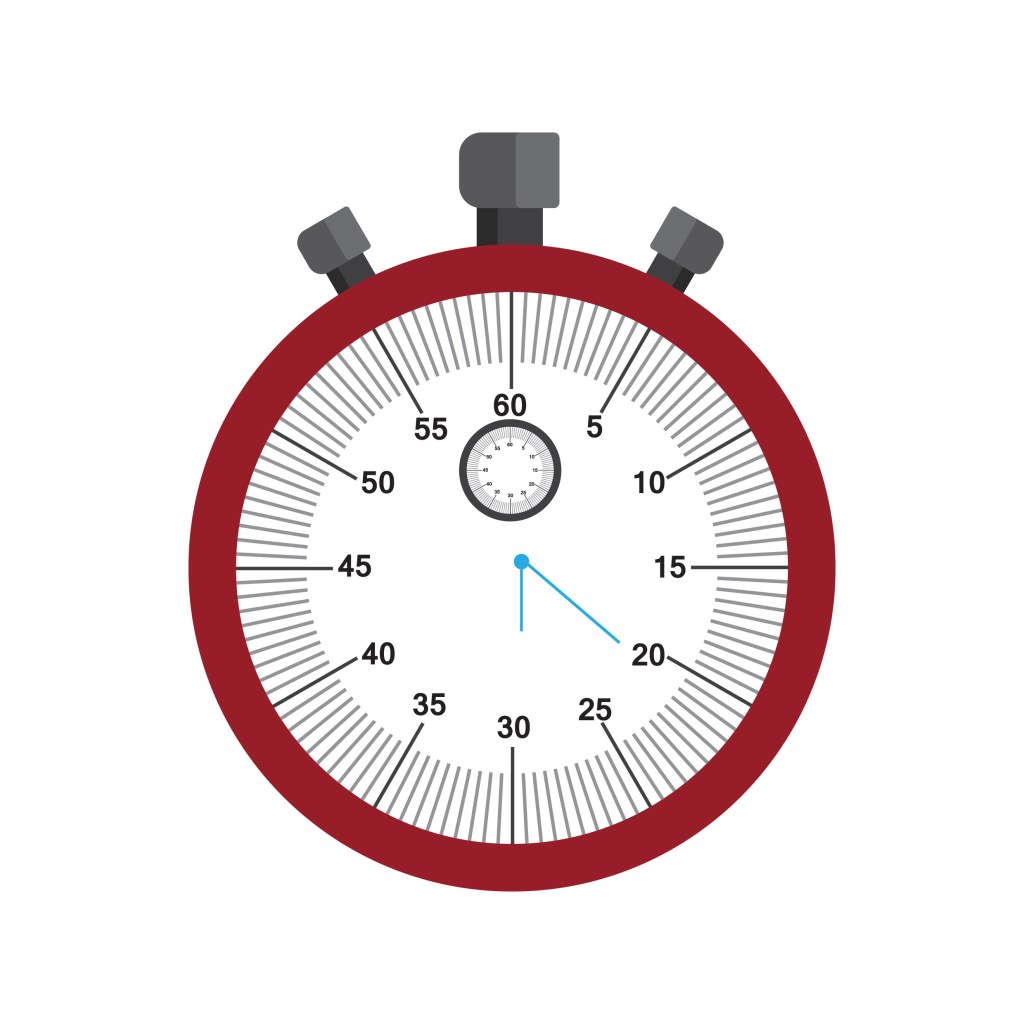

During the opening credits of Ladybug Ladybug (1963), a blurry image of a hand holding a stopwatch comes into focus. It’s simply the elementary school principal, John Calkins (William Daniels), telling students that their achievement test has ended. However, when the civil defense alert sounds in his office and the yellow light means there will be a nuclear attack in one hour, time has a different urgency.

The film seems as if it’s told in real time because it suffers from the same affliction of others that use the storytelling device: it often feels slower than how real time unfolds. And speaking of “real,” nobody knows if the alert is real or not. Perhaps the nuclear threat was not as great in 1963 as it was a few years earlier, but Calkins is reluctant to believe they are truly under threat and therefore doesn’t act immediately.

The teachers and students think it’s another drill and are lackadaisical about going through another one again so soon. While the characters aren’t bothered early in the film, the audience watching the move are. We have to assume it’s real and grow uncomfortable waiting for them to take the possibility seriously. Finally, the children gather on the playground and are divided into their “go home” groups.

One group boards a bus that heads in one direction. Another is led on foot by Mrs. Andrews (Nancy Marchand) in the other direction. One student lives further from the school and his father drops him off and picks him up everyday, so he gets to stay with the principal, his secretary, Betty Forbes (Kathryn Hays), and the dietician, Mrs. Maxton (Jane Connell) as they continually try to phone for more information, but keep getting busy signals.

After establishing the plot, Ladybug Ladybug alternates between Mrs. Andrews and her group of children walking down a rural road, and the frantic activity at the school. For the former, the further they get, the more the children question why the drill hasn’t ended; they’ve never gone this far. Likewise, their teacher gradually unravels before our eyes. By the time she stumbles and breaks a heel, she’s practically in shock.

While not exactly action packed, the best part of the movie for me is the speculation of the children once they accept that there might really be a bomb about to drop. As young as they are, they mostly repeat things they’ve heard from their parents. It’s fascinating hearing adult words coming from the mouths of babes, particularly since they may not understand what they’re saying.

Eventually, the children make it to their homes and find different reactions from their parents or guardians, if they’re even home. They mostly face disbelief. If there was really an emergency, wouldn’t they know? The radio stations are still playing peppy 1960s tunes. One group of kids ends up in a bomb shelter without parental guidance and prissy Harriet (Alice Playten) takes charge, establishing rules and rationing water.

This, of course, creates conflict not unlike the one we discussed last week in This Is Not a Test. It’s again fascinating to experience how a collection of children behaves just like their adult counterparts. This time they’re independent, though, acting by nature rather than nurture. It’s all thought-provoking, but not necessarily effective at telling a consistently compelling story.

What do we make of the ending, then? It’s worth watching to find out what happens, so I won’t give any spoilers. There is joy and there is tragedy. These are the final two lessons of Ladybug Ladybug. First, we must depend on each other; we are not alone on this planet. Second, information is everything. Having it means the difference between life and death. Sadly, there’s not much of a message about hope.

Leave a comment