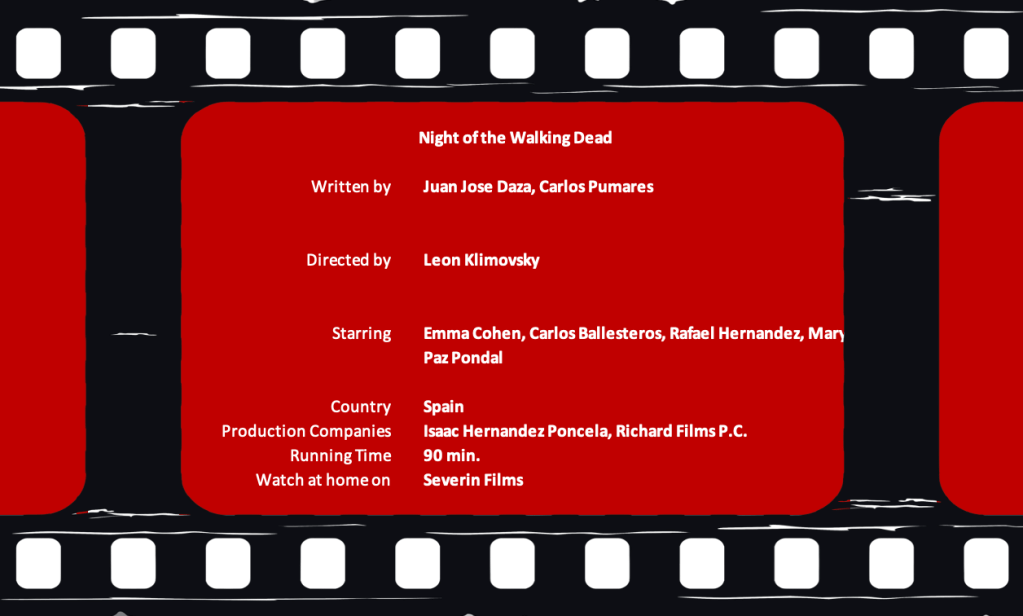

In Night of the Walking Dead (1975), director Leon Klimovsky borrows one of the techniques he used in The Werewolf vs. the Vampire Woman (1971), but for only one scene. It’s a type of slow-motion effect that doesn’t look like slow-motion, but like vampires eerily moving in their own unique way. Night of the Walking Dead would have benefited from a little more style like this. As it is, it’s a less interesting-looking movie focusing on the romance, and is more suited to its original Spanish title, El extra no amor de los vampiros or its English translation, Strange Love of the Vampires.

If the romantic aspect appeals to you, Night of the Walking Dead does it better than most Euro-vampire movies. That’s not to say it’s entirely original, though. In fact, so many plot points, situations, and even music cues seem borrowed from other productions about vampires. Written by Juan Jose Daza and Carlos Pumares, I’m willing to bet one or both were familiar with Dark Shadows, if not fans of the television soap opera that ran from 1966-1971. It worked for me. I enjoyed recognizing bits and pieces and admired the way they were assembled into a coherent story.

The movie begins with one of the strangest opening credits sequences I can remember. It’s like the Barack Obama ‘Hope’ poster come to life, with stylized red and blue colors sharing the screen, then layered with some Corman/Poe oozing colored liquids. On top of that, it looks like we’re watching the movie on an antenna TV in the 1980s:

It’s kind of fun, but is ruined by horribly screeching guitar music that made my ears bleed. Luckily it doesn’t continue for the rest of the film, or I would have been physically unable to continue watching it. The music is credited to Maximo Barratas, but like the story elements, it seems cobbled together from other movies. We have thin orchestral melodies, spooky theremin scales, flute solos, jazzy crime story riffs, and finally a manic tune to contribute to the suspense. Had I realized how erratic the score would be, I may have turned down the volume. I mean, it’s spoken in a foreign language; I can read the subtitles!

There’s one brief combination of musical elements right out of Dark Shadows, and the return of Count Rudolph de Winberg (Carlos Ballesteros) is reminiscent of the return of Barnabas Collins. There’s no reincarnation element, but Catherine (Emma Cohen) seems like (and even says) she’s drawn to him for some reason. This vampire really loves her. He refuses to bite her and tells her it’s up to her if she wants to remove her cross necklace so he can do it. He doesn’t protect her from anything, though, inviting her to the once a year party where all the bodies of the dead rise from their graves to celebrate.

The Count explains that his species is “persecuted and mistreated,” so they deserve a little fun every twelve months. This includes hanging the handsome Jean (Baringo Jordan) from the ceiling by his feet so they can poke him with the point of a knife and collect his blood in goblets as it pours out like a sink faucet. My favorite part of the film happens in this sequence. Jean is Catherine’s former lover whom she recently caught cheating on her with her chamber maid, Maria (Vicky Lusson.) The Count gives Catherine an opportunity to set him free, but she claims she’s never seen him before.

The dramatic thread running through Night of the Walking Dead is that Catherine is dying. She doesn’t seem to want to live; however, becoming the Count’s vampire bride would probably extend her life. Is that why she wants to live with him forever? Or is she just a bit evil herself? We’ve seen her spying on pairs of lovers as they frolic in their bedrooms or in the barn, then use the information to blackmail them. Or is she simply so tired of living in a world where she has seen death and betrayal that she wants to escape to another one?

You know it’s a strange and unique vampire movie when the familiar parts of the story are treated like a subplot. There’s the recent vampire attacks that rile the villagers, a doctor who doesn’t believe in superstition, and the father of a dead girl rallying the troops to exhume bodies from the cemetery, hammer nails into their foreheads, and let them turn to dust in the sunlight. It’s all secondary to the Count and his potential bride, Catherine, who is not a damsel in distress, but a woman who may not know what she wants, but is determined to have it anyway.

Leave a comment