October 9, 1962

- NASA civilian test pilot John B. McKay takes an X-15 to 39,200 miles,

- Uganda became independent from the United Kingdom, and…

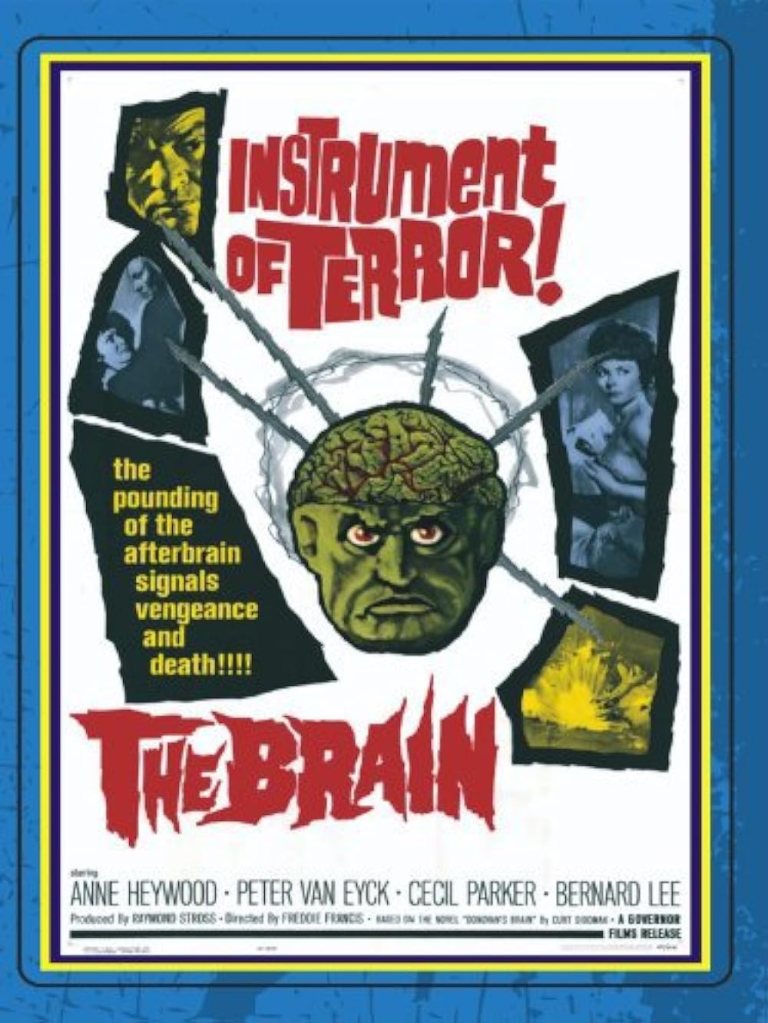

For some reason, I’ve never been fond of Donovan’s Brain… or any of its versions. When I watched three of them for discussion on the podcast, I rated Donovan’s Brain (1953) average, The Lady & the Monster (1944) slightly below average, and The Brain (1962) slightly above average… so it was my “favorite.” So unattached am I to the story, though, that even when I rewatched it, I forgot it was an adaptation of Curt Siodmak’s novel.

This was before and after watching the movie. I now recall (vaguely), but am reminded through what little research I can do, that The Brain is quite faithful to Donovan’s Brain. (Or is Donovan’s Brain faithful to The Brain? The Brain came first; it’s just not as well known or loved.) The primary difference here is that when the disembodied brain of a tyrant tycoon exercises telepathy to control the doctor who harvested it, it’s to play junior detective and learn who planted an explosive in his airplane.

The concept reminds me of D.O.A. (1950), in which a man (Edmond O’Brien) who’s been poisoned tries to solve his own murder before he dies. Here, the investigation is conducted by Dr. Peter Corrie (Peter van Eyck) in various states of control by the tyrant tycoon, Max Holt, whom we see only in flashbacks and from behind.My problem with the details is that Corrie starts asking questions before he’s being controlled and it seems like that would put him at risk for discovery of the crimes he’s committed.

That almost happens when the mortuary attendant suspects wrong-doing and tries to blackmail Corrie. But Corrie has Holt’s body cremated so there’s no evidence against him.

I’m not sure about Corrie’s day job, but when Holt’s plane explodes in the sky nearby, he and his associate, Dr. Frank Shears (Bernard Lee), are called to the scene to assess the bodily damage. This allows them to take the still-breathing Holt to Corrie’s in-home lab so that discussions of morality can occur. Shears reminds Corrie that it would be kinder to put the dying man out of his misery, then asks a rhetorical question as Corries begins operating. “You’re not going to experiment on a dying man?!?”

At this point, the doctors don’t know Holt’s identity. This admittedly adds intrigue to the plot, especially as clues are dropped through television news reports and rumors spread about a second explosion before the one that blew the plane out of the sky.

We then meet Holt’s surviving family members and other suspects, primary among them his daughter, Anna (Anne Heywood) and her brother, Martin (Jeremy Spenser.) It’s one of those situations where everybody has a motive and everybody accuses someone else. However, I was again confused by who was conducting the investigation, Corrie or Holt. Up to this point, the disembodied brain is exercising more influence over the mad scientist, yet he doesn’t know the identity of someone on a list of names to which Holt would have had access.

You’ve got to admire the single-mindedness of the characters in the screenplay by Harry Spalding. They each want something and any logical actions or reactions are irrelevant. Corrie wants to experiment. Holt wants to solve his murder. This becomes a little unrealistic, though, when none of the suspects seems to question that Holt has in some way returned from the grave and that Corrie is involved.

Even with all the coincidences, The Brain still tells a compelling story. It’s just that it’s told through strictly B-movie conventions. There seems to be enough material to create something more substantial, so I suppose that’s where some of my disappointment arises. It could have been really good, but it just doesn’t quite make it.

Leave a comment